Part 1 of 3

What is it that makes a choir’s singing irresistible? Beyond insisting on the obvious basics of clean intonation, resonant vowels, and sparkling diction, is there anything else a conductor can do to increase the excitement level produced by a choir’s performance? And if so, how can the skills needed to create this excitement get taught in the limited time typically available for weekly rehearsals?

it that makes a choir’s singing irresistible? Beyond insisting on the obvious basics of clean intonation, resonant vowels, and sparkling diction, is there anything else a conductor can do to increase the excitement level produced by a choir’s performance? And if so, how can the skills needed to create this excitement get taught in the limited time typically available for weekly rehearsals?

In my experience, three qualities characterize exciting choral singing: dynamic range, articulative variety, and meaningful phrasing that matches the musical setting of the text. These attributes have three things in common. They proceed from the conductor’s understanding of the emotional and story-telling content of the score, along with its vocal and musical demands. They are shaped and reinforced by the conductor’s gestural choices. And they require intentional physical investment by individual singers in responding to the gestural cues the conductor provides them.

In other words, exciting choral singing begins in the conductor’s mind, gets communicated by gestures the conductor gives in rehearsal and performance, and comes to life in the embodied choices of the singers. As the venerable Helen Kemp never tires of reminding us, “Body, mind, spirit, voice—it takes a whole person to sing and rejoice.”

* * *

Let’s begin with dynamics, since these are usually marked in the scores our choirs hold, even if they don’t often actually sing many (or most) of them. The sad reality is that the vast majority of choirs are monodynamic: they generally settle for an amplitude level that hovers around mezzo forte, and seldom sing outside of that comfort zone. Choirs which do make an effort to sing with dynamic variety often experience a different problem: they frequently crescendo too late and decrescendo too soon, as though unwilling to leave the mezzo forte comfort zone until they absolutely have to, and are bound and determined to settle back into it just as fast as they possibly can.

Interestingly, the cause of this problem also holds the seeds of its solution. Monodynamic choirs settle because they don’t aurally or physically recognize the difference between forte and piano singing. They don’t know how to make the difference happen, and it’s not really fair for us to expect them to deliver what they don’t understand. They don’t know how—and they won’t, unless and until conductors equip them to enjoy the full range of dynamics they can create.

One important part of the solution is to establish baseline awareness as a matter of habit. One simple way to accomplish this is to periodically stop in rehearsal and ask, “On a scale of 1 to 10, 1 being the quietest you can sing (let’s call it ‘piano’) and 10 being the fullest sound you can make (let’s call that ‘forte’), where are you right now?” Allow your singers to tell you where they think they are: that in itself is useful information to elicit from them, and it begins to get them used to taking direct ownership of the sounds they’re creating.

Perhaps your choir says, “We’re at about a 4 or a 5.” Now, invite them to look at the scores in their hands, and ask, “And at what level on a scale of 1 to 10 should we be singing?” If the music calls for forte, for example, your singers should answer somewhere between 7 and 9. “Okay, then,” you say, “let’s go back over that passage and sing it at an 8.”

The whole process as I’ve just described it takes at most 30 seconds, and once it’s part of your choir’s DNA, it becomes a game that yields immediate and tangible results. To lock it into place—and just as important, to get your singers accustomed to associating gestures with dynamics—regularly vary the size and weight of your gestures during warm-ups, and insist that they sing what they see. “How big a sound am I asking for: a 3 or a 7?” I frequently ask my choirs at the beginning of rehearsal as we warm up. Another effective approach is to take a passage that the choir knows well, even a familiar unison melody (plainsong works very well for this), and have them sing it at different dynamics: first at a 3 or 4, and then at a 7 or 8, based on whatever the gesture is that you’re showing them in the moment.

* * *

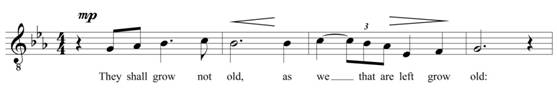

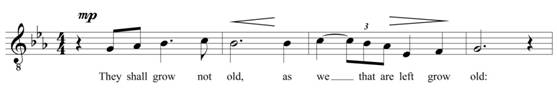

Singing dynamic shapes like crescendi and diminuendi is sometimes made more challenging than it needs to be by composers who mark scores incompletely. Consider the following example, from the opening of Michael Sammes’ moving Remembrance Day anthem, For the Fallen:

How full should the choral sound be at the peak of the crescendo in this phrase? It’s anyone’s guess. This is where pencil work can help. Depending on how long the phrase is, and what the tempo of the music happens to be, I will ask my singers to mark not only the arrival point in their music, but various points along the way as well, like this:

(3) (4/5) mf (6) (4/5) (3)

You may have noticed that nowhere in this discussion have I defined forte as “loud.” This is not accidental. Choirs that equate forte with loudness frequently fall prey to bad vocalism, confusing forte with throaty, shouty, tight singing, and piano with breathy, thin, unsupported vocalism. Both of these errors in understanding can lead to out-of-tune singing as well as do significant vocal harm.

Forte singing is full singing: full bodied, fully breathed, fully supported. Like all good singing, it is grounded deeply in the body and created freely in the throat. Phonation, remember, is the effortless transformation of breath energy into vibration: the energizing of the vocal folds is instantaneous and doesn’t create tension or any sense of strain. It’s effortless in the throat (which is why I avoid terms like “attack” or “producing the voice” and prefer “releasing the voice” or similar words to describe the onset of phonation). There is work to be done, certainly—but that work is done elsewhere, deeper in the body, with the abdominal muscles primarily. Forte is a full body experience, not a loud one.

But here’s the astonishing thing: piano singing works almost exactly the same way! It uses the same mechanics: breath energy, phonation, abdominal muscles. This is why I prefer to describe piano as “intense,” instead. There is nothing “soft” about it. As I periodically remind my choirs, “Piano singing is just forte singing sung quietly—with less volume but a lot more intensity.” Because phonation is always linked to the breath, one exercise I find helpful is to ask my choirs to breathe in the dynamic they intend to sing. “Have a forte breath,” I’ll say. “Now, have a piano breath” (we don’t “take” breaths in my choirs because that often produces a sense of clutching that results in audible sound and dries out the vocal tract; we “have” breaths or “allow” breaths, instead). This little etude can also be linked to gesture, simply by asking the choir to breathe in the dynamic that your preparation gesture suggests.

Recently, I’ve become fond of an image I learned from Dr. Pearl Shangkuan, professor of music at Calvin College in Grand Rapids and conductor of the Calvin College Alumni Choir. She describes piano singing as a chocolate-covered macadamia nut: piano on the outside (that’s the chocolate coating), and forte on the inside (the macadamia nut). The interesting thing about this wonderful image is the physical truth it communicates. Which is the larger principal component—the nut or the coating? The nut, of course: the forte that always lives at the heart of all true piano singing.

* * *

If we teach our singers well; if our gestures evoke the range of dynamic possibilities; if we regularly invite our singers to pay attention and take mindful, attentive ownership of the dynamics they see and the sounds they release, then we have come a long way in creating real excitement in our choral singing. It is a big step toward becoming true choral artists.

NEXT TIME: Creating musical excitement through choral articulation.

Dr. Gerald Custer is a choral conductor, award-winning composer,

teacher, and author. You can email him at custer@wayne.edu.